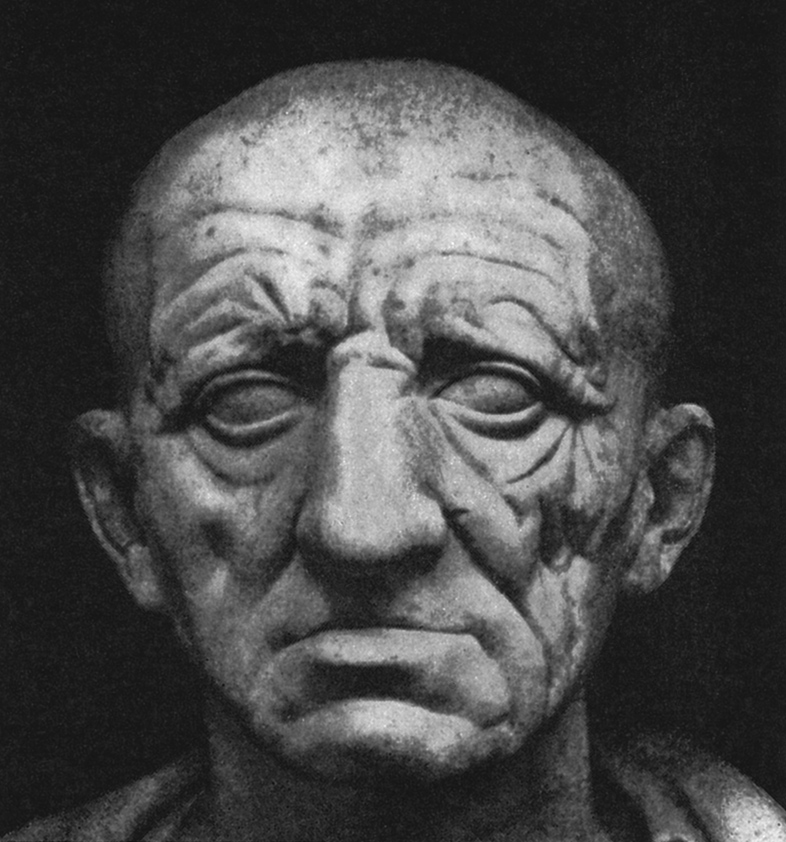

Bust of Cato the Elder

Introduction

Based on its mention in three letters to Atticus, Cicero’s friend, the earliest of which was written on 12th of May, 44 BC, it is assumed that this work was composed in April of that year.

In this work, Cato Maior De Senectute (Cato the Elder on Old Age), commonly known as On Old Age. Cicero chooses as his mouthpiece and principal speaker for this fictional dialogue, Marcus Porcius Cato (Cato the Elder), famous for signing off after every speech, no matter how trivial, with the phrase: “Carthago delenda est” or “Carthage must be destroyed!” Cato died in 149 BC reaching the grand old age of 85. Cicero reasons he chose Marcus Cato because he wanted to be taken seriously compared to some philosophers whose style used mythological characters as their mouthpiece such as with the Aristotelian philosopher Aristo of Ceos, who used Tithonus, prince of Troy and lover of the goddess Eos, as his mouthpiece.

The other participants are two younger speakers: Scipio Africanus the younger and Gaius Laelius. The dialogue is Cicero’s attempt on using philosophy to combat objections that old age is a miserable time of stagnation in our lives and positing forward arguments for its advantages.

Before writing this article I had to decide whether to use the old James S. Reid translation or the modern Phillip Freeman translated version.

So here, compare this passage in the James S. Reid version:

“To myself, indeed, the composition of this book has been so delightful, that it has not only wiped away all the disagreeable of old age, but has even made it luxurious and delightful too”

To Phillip Freeman’s version:

“In fact, I’ve so much enjoyed composing this work that writing it has wiped away all thoughts of the disadvantages of growing older and made it instead seem a pleasant and enjoyable prospect.”

By the way, both of these passages are about Cicero’s enjoyment of reviewing the contents of his work. What comes to mind is that of a sculptor having finished his statue, taking a few steps back, with tools still in hand, gazing up marveling at the accomplishment of the fruits of his labour.

Let’s compare another passage and again with starting with the James S. Reid version:

“Scipio: Many a time have I in conversation with my friend Gaius Laelius here expressed my admiration, Marcus Cato, of the eminent, nay perfect, wisdom displayed by you indeed at all points, but above everything because I have noticed that old age never seemed a burden to you, while to most old men it is so hateful that they declare themselves under a weight heavier than Aetna.”

Phillip Freeman’s version:

“Scipio: When Gaius Laelius and I are talking, Marcus Cato, we often admire your outstanding and perfect wisdom in general, but more particularly that growing old never seems to be a burden to you. This is quite different from the complaints of most older men, who claim that aging is a heavier load to bear than Mount Etna”

Reading the passage from the James S. Reid translation didn’t describe Mount Etna as ‘Mount Etna’ instead ‘Aetna’ was put in. Which would fly over the heads of the geographically challenged.

So after reading the few other passages up to this point I decided to go with the modern Philip Freeman translation. The modern translation, other than the translation of the work itself, comes with a brief introduction. However, what made it worthwhile are the notes scattered throughout the book giving the work more insight to the work’s background information. In this article, I will address the first part of the work which are the preliminary and introductory conversations between the three persons.

On Old Age

The dialogue starts off with Scipio complementing Cato’s ‘outstanding and perfect wisdom’ and lauding that old age has seemed not a burden to him because in contrast other old men complain about their seniority with a burden heavier than Mount Etna.

Cato thinks every age would be burdensome to those who lack the resources to ‘live a blessed and happy life’, the man goes on:

“But for those who seek good things within themselves, nothing imposed on them by nature will seem troublesome. Growing older is a prime example of this. Everyone hopes to reach old age, but when it comes, most of us complain about it. People can be so foolish and inconsistent.”

Telling people to ‘seek good things within themselves’ is implying to me to mean we must seek self-improvement of the mind by means of wisdom. However, what caught my attention later in the passage was this statement: ‘Everyone hopes to reach old age’. It’s a generalisation that many of us modern folk have heard more than once, but from this statement I have a cynical view: when the young say they hope to live to an old age what they really mean is that they wish to delay death as long as possible, not wishing to die young, they put old age in the cupboard as something to deal with in the winter years of their lives.

I don’t disagree with Cicero often, but in this case I do. It’s not that people hope to live to an old age, it’s that they hope to live a life of ample longevity to mask the inevitability of mortality. But I agree on the latter part of that quote – instead of accumulating the wisdom from philosophy to cope with it, when people do reach old age having hoped in younger years to reach it they then proceed to complain and be miserable. This I agree is a foolish choice.

Complaining about old age

This feeling of old age as creeping upon us is a sentiment alive and well today as it was back then, Cato speaks:

“They say that old age crept up on them much faster than they expected. But, first of all, who is to blame for such poor judgment? Does old age steal upon youth any faster than youth does on childhood? Would growing old really be less of a burden to them if they were approaching eight hundred rather than eighty?”

It is not the advancing years themselves Cato is addressing as the problem; but the dissatisfactory realisation that one is getting older. We know that medical science has improved our life expectancy compared to previous centuries. For arguments sake, let’s imagine this scenario. Let’s say science has extended, by means of genetic engineering, the human lifespan in one individual to eight hundred years. Would this individual be consoled, at age four hundred let’s say, by the fact that time is still be slipping away? That they are still getting older?

Nature’s will

Cato in this passage below,

“So if you compliment me on being wise – and I wish I were worthy of that estimate and my name – in this way alone do I deserve it: I follow nature as the best guide and obey her like a god… Fighting against nature is as pointless as the battles of the giants against the gods [In Greek mythology, the race of giants rose up against the gods of Olympus only to be defeated]”

Cato likens life as a drama which nature has fully planned out for all of us. Cato embraces the principle of amor fati, love of one’s fate, whether that be good or bad, he stoically accepts wholeheartedly.

The woe of former consuls

Gaius Salinator and Spurious Albinus (who were contemporaries of Cato), constantly complained about old age because it snatched away the sensual pleasures of life making it not worth living; plus experiencing neglect by people who once paid attention to them. Cato on hearing this offers proof to the contrary; his proof? himself! He also says that he has known many others who have grown old and have not missed the ‘binding chains of sensual passion’ and have enjoyed the company of friends without neglect. The blame lies not in old age, but instead on the person’s character.

“Older people who are reasonable, good-tempered, and gracious will bear aging well. Those who are mean-spirited and irritable will be un-happy at every period of their lives.”

Can Wealth help?

Laelius asks:

“What if someone were to say that your wealth, property, and social standing – advantages in life that few people possess – are what have made growing older so pleasant for you?”

[Since those who have reached old age are often wealthy because they have had more time to accumulate and save wealth.]

To this point raised, Cato concedes that being poor is not a light burden – but if someone is a fool, being one who blames old age instead of character on the woe of getting older, then all the money in the world won’t make aging easier. One can enjoy the fruits of accumulated wealth over the years; but if the mind is not at peace because one is rolling into old age then wealth can only provide so much enjoyment and no matter how rich you are; you can’t buy another life…

From the Stoic perspective this is all owing to one’s mind not knowing how to live well because of being so undeveloped and untrained by a neglect of philosophy; ‘which is the medicine of our souls’ as Cicero described philosophy elsewhere.

Be like Plato!

Cato remarks on the campaigns of Quintus Fabius Maximus during the Second Punic War, who he himself accompanied when just a young man. Maximus campaigned while still ‘getting on’ in old age but despite that he wore down Hannibal’s youthful exuberance by his persistence. Now not everyone can live and tell the tale to their countrymen on how they conquered land for their people and basked in the glory as a national war hero.

Cato however says there is another kind of old age ‘the peaceful and serene end of a life spent quietly, blamelessly, and with grace.’ What was Cato’s inspiration? It was Plato. For Plato lived out the winter phase of his life like this, continuing in his writing and reflecting on philosophy. It had to be asked though is striving for something really a characteristic of youth? Why not strive for wisdom instead? The Stoics would certainly have recommended this way of spending old age.

Before Cato goes on he quotes Quintus Ennius, Roman poet and contemporary of Cato:

“Like a courageous steed that has often won

Olympic races

in the last lap, now weakened by age he

takes his rest”

The four reasons why old age is considered miserable

Now comes to the main part of the work; Cato’s defence of old age. Cato lists out the four objections associated with old age and answers each one in turn. Each objection will be addressed in separate articles: