Everyone who studies or has an interest in philosophy has heard of Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Descartes, Voltaire, Nietzsche, Hegel, Marx and modern philosophers too like Daniel Dennet. I like to guess and think of these people as the popular philosophers because they are the household names that most often show up everywhere on the interwebs when philosophy is discussed. Browse different philosophical websites and forums and you will see that there are countless articles and quotations from this popular pantheon of philosophers. However, there’re other philosophers out there that have not been popularised and therefore their ideas and themselves even, have become esoteric. This article is about one.

His life

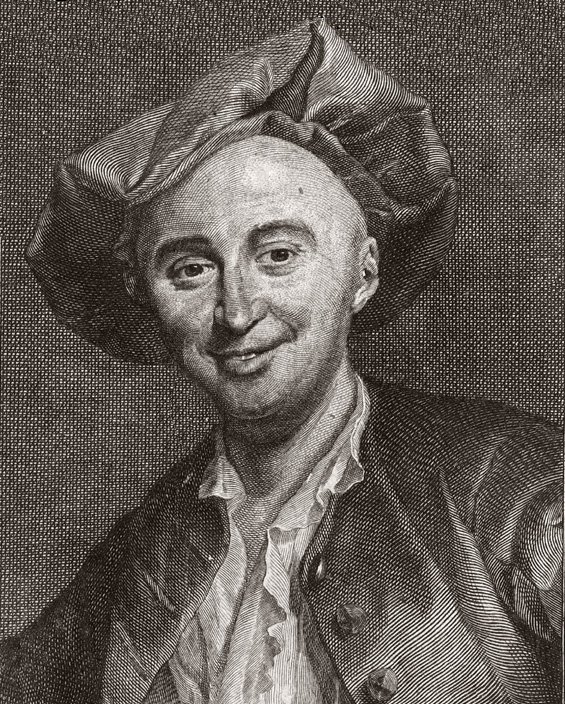

His full name was Julien Offray de La Mettrie (1709-51), 18th century era French physician and materialist philosopher. Not surprising, that the sort of philosophy a physician would turn out to be is a materialist. As being a physician would be a practical discipline concerned with studying the body in all its corporeal glory and correct its ailments.

La Mettrie was born in Saint Malo, Brittany in 1709, briefly put, his father wanted him to become a priest however La Mettrie’s talents were thought best served in medicine studying alongside philosophy too in Harcourt College, Paris in 1725. In 1733, he received a degree as Doctor of Medicine was transferred to Leiden and for the following year he attended lectures under the pioneering Herman Boerhaave the ‘Dutch Hippocrates’ his education complete, he starts medical practise in Saint-Malo his birthplace.

For the years Between 1743 and 1746 he served as an army doctor in the War of the Austrian Succession, He accompanied Louis of Gramont, the Duke of Gramont with the esteemed position as surgeon of the French guards. At the Siege of Freiburg, during the campaign La Mettrie came down with a fever that almost killed him however, despite this high fever, La Mettrie used the, what I would call, technique of naturalistic mindfulness to simply observe the state of his body. This introspection of his corporeal body, despite the torment and escapades of hallucinations, he began to notice that his cognitive processes quickened as a result, he thought this due to the increased blood circulation brought about by the fever which led him to believe that the body, especially the brain is the seat of the soul or consciousness.

Here is an excerpt from Frederick the Great of Prussia’s Eulogy on La Mettrie (source in citations) he comments on the fever that gripped La Mettrie so vividly.

“Julien Offray de la Mettrie During the campaign of Freiburg, La Mettrie had an attack of violent fever. For a philosopher an illness is a school of physiology; he believed that he could clearly see that thought is but a consequence of the organization of the machine, and that the disturbance of the springs has considerable influence on that part of us which the metaphysicians call soul. Filled with these ideas during his convalescence, he boldly bore the torch of experience into the night of metaphysics; he tried to explain by aid of anatomy the thin texture of understanding, and he found only mechanism where others had supposed an essence superior to matter. He had his philosophic conjectures printed under the title of “The Natural History of the Soul.” The chaplain of the regiment sounded the tocsin against him, and at first sight all the devotees cried out against him.”

He would remark in later works of his many experiences of seeing death during the war:

‘I saw thousands of soldiers die – a sorry sight!- in those great military hospitals of which I was in charge in Flanders during the last war. Pleasant deaths such as those I have just depicted seemed to me much rarer than painful deaths. The most frequent ones happen unawares. We leave the world as we come into it, without realising it.’

In 1745, Natural History of the Soul was published which was a materialist account of the soul. The authorities and the church were having none of that, saying that a physician espousing blasphemous doctrines was not to be trusted in healing the French guards. He then later criticised the medical profession for their incompetence and vanity, which, let’s be frank, did not improve the already dire situations that he already found himself in. With the combined ire of the church, the authorities and fellow physicians, La Mettrie was forced to escape to Holland to in order to evade possible imprisonment. This is where he published his notorious book Machine Man; but he found no peace in Holland publishing this work and was exiled again.

In 1748, he found refuge in Berlin under Frederick 2nd of Prussia and was given the role of physician in the court he also became a member of the Berlin Academy of Sciences.

During his everyday role as physician, a visiting French ambassador, Tirconnel was very grateful to La Mettrie for curing him of an illness, and gave a feast to celebrate his recovery. What happened next is a typical example that contributes to the stereotype that atheists/naturalists/materialists are hedonists.. His eyes were bigger than his stomach in this regard trying to show his great constitution by eating copious amounts of food particularly pheasant paste which made him develop his final fever and end.

Emperor Palpatine’s commentary deserves a bold mentioning here:

‘Ironic. He could save others from death, but not himself. …’

His philosophy

What made him unique was that he was not only a philosopher but also a physician and an accomplished one at that! In the time he lived the act of espousing materialist philosophy was blasphemous. La Mettrie’s works were often burned, the ‘unholy’ pages were condemned to the embers as a part of a spectacle of religious fervour. This public condemnation in France was not particular to La Mettrie though, as other works of natural philosophy especially Baron D’Holbach’s work, System of Nature, was condemned by the French parliament and cast into the embers too. Despite intimidation, La Mettrie was not dissuaded into abandoning his philosophy he continued to soldier on and simultaneously doubt the existence of an immortal, immaterial soul a cornerstone of Christian theology.

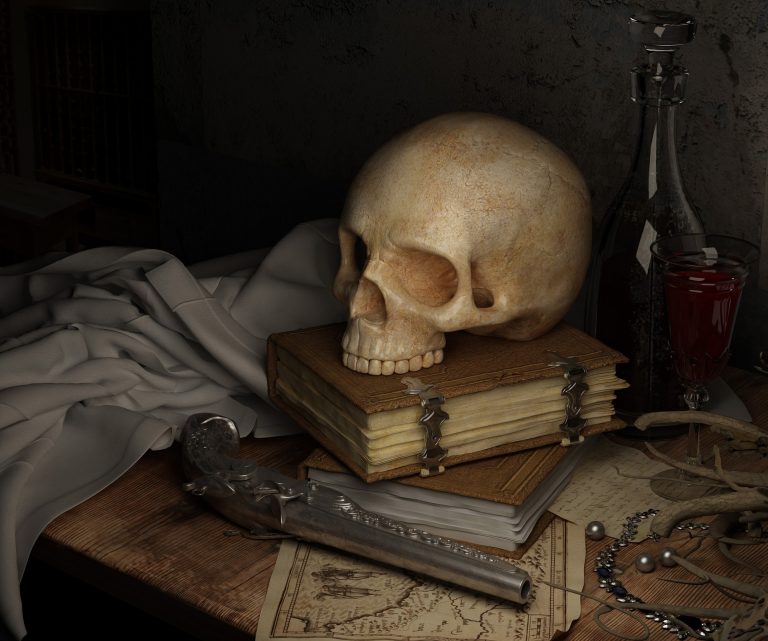

If the transition from life to death is from being to nothingness why invest fear and significance to the absence of nothingness? That is what the epicurean asks. His disposition towards death was indeed that of an epicurean, best of all expressed in his The System of Epicurus which goes into the most detail on his thoughts on death including even accustoming himself in imaging his own death. His attitude towards death:

‘If you fear death, if you are too attached to life, your last breath will be terrible; death will act as your cruellest torturer. It is torture to fear it.’

‘To tremble at death’s approach is to be like children who are afraid of ghosts and spirits. The pale spectre can knock on my door when it wants; I shall not be terrified of it. The philosopher alone is a brave where most brave men are not brave at all.’

‘Death in the nature of things is only what zero is in arithmetic’

With a big F U and shining conviction he clearly states his view on an afterlife:

‘Death is the end of everything; after it, I repeat, there is a void, an eternal nothingness. Everything has been said, and everything has been done. The sum of good is equal to the sum of evil. There are no more cares, no more problems, no more characters to play: the comedy is over.’

From viewing death we look at what La Mettrie saw in life, mentioning the implications of the conservation of mass and the law of entropy all summed up in one quote as the man says here:

‘How fleeting is life! The shapes of bodies sparkle for as long as topical songs are sung. Men and roses appear in the morning and have vanished by nightfall. Everything is replaced, everything disappears and nothing is destroyed.’

Often throughout his works he had mixed feelings of Rene Descartes both admiring and criticising him at the same time. Good examples are found in his Treatise on the Soul, one of his major works, In this La Mettrie espouses his materialism by rejecting the dualism of Descartes and the other notion that Descartes ascribed to matter, namely, as having a property only limited to extension and that the motion of matter was caused by god, the prime mover, over this La Mettrie face palmed and attributed this to Descartes pandering to the ‘light of faith’. In La Mettrie’s eyes, matter is more than just the simple extensions of the three dimensions it has the power to ‘acquire motive force and the faculty of feeling’ which implies consciousness.

‘The Soul [consciousness] and the body were created together in the same instant and as if at a single brush stroke.’

‘The essence of the soul of man and animals is, and will always be, as mysterious as the essence of matter and bodies.’

La Mettrie criticises Descartes further in the latter’s claim that animals were emotionless machines. La Mettrie asserts that both men and animals are not emotionless automatons but rather feeling automatons. He hypothesised that the cartesians thought this because animals do not have a human appearance. La Mettrie bridged the gap between man and animal by pointing to comparative anatomy that we have similar sense organs and therefore similar faculties of feeling. However nevertheless La Mettrie always maintains in his philosophy that feelings and emotions are but the workings of the ‘springs and gears’ of a living machine because these faculties only appear in organised bodies.

Even though at the time atoms as the essence of matter as it is understood by modern science nowadays was not confirmed to exist, La Mettrie nevertheless justifies this ignorance:

‘Although we have no idea of the essence of matter, we cannot refuse our consent to the properties which our senses discover in it.’

Typical of what characterised La Mettries’ materialism is the rejection of the existence of absolute moral values epitomized in his work anti-Seneca to which it argued good and evil are created by religion for the needs of society and have no other validity. This later frustrated other materialist attempts towards constructing a secular morality in competition with theological morality. For this La Mettrie was described as a ‘lunatic’ by his ‘comrades’ in the materialist camp. He fuelled philosophical discourse for the years to come by contributions. He lived and poured the honey of his philosophical thoughts into his works and is remembered for being the maverick philosopher who rocked the boat, not with just theology, but with dualism and moral philosophy too. His critiques, taunts and polemics along with his radical materialist philosophy cemented him as being one of the principal French enlightenment philosophers standing along with the likes of Voltaire and Denis Diderot.

Citations

Frederick the Great of Prussia’s Eulogy on Julien Offray de la Mettrie:

https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/la-mettrie/eulogy.htm

La Mettrie: Machine Man & Writings (Cambridge Texts in the History of Philosophy)

http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Julien_La_Mettrie